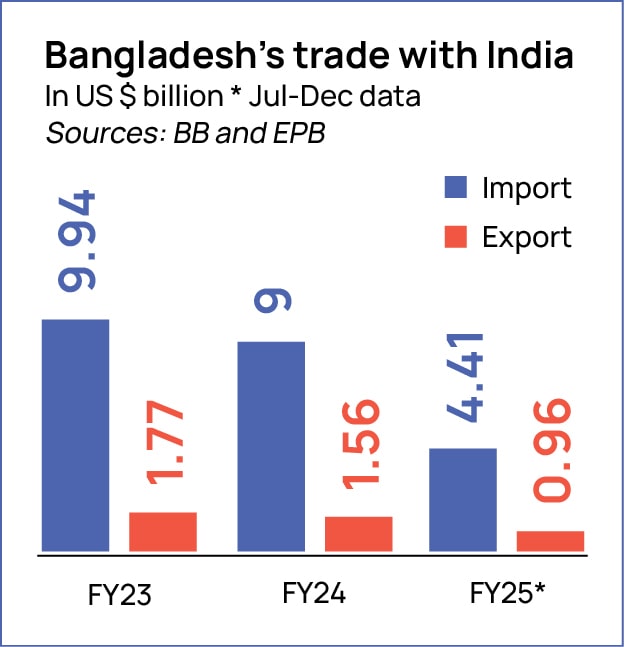

What started as political friction is now spilling over into trade and the consequences are starting to sting. India and Bangladesh, two neighbours with a deeply intertwined trading history, are seeing their economic ties going through a rough patch.

It wasn’t long ago that things looked much brighter. Both sides were seriously discussing a free trade agreement, something that could have been a real game-changer. The World Bank even estimated that it could boost Bangladesh’s exports to India by nearly 297 per cent and India’s exports by 172 per cent.

To reduce its dependence on the US dollar for foreign trade, Bangladesh also began using the Indian rupee for trade with India in 2023.

But now, that progress is on hold.

In a major policy shift, India pulled the plug on a key transshipment facility that once allowed Bangladesh to route export goods to other countries using Indian land customs stations, ports and airports. This arrangement, in place since June 2020, ended on April 8 and it’s already sending ripples through Bangladesh’s RMG industry. With this move, Bangladeshi exporters, especially those eyeing Europe and West Asia, now face a bumpier, more expensive logistics ride.

Until recently, it was a cost-efficient route where cargo moved from Dhaka through Benapole and Petrapole to Delhi, with Indian trucks transporting the goods at rates as low as 70 cents per kilo.

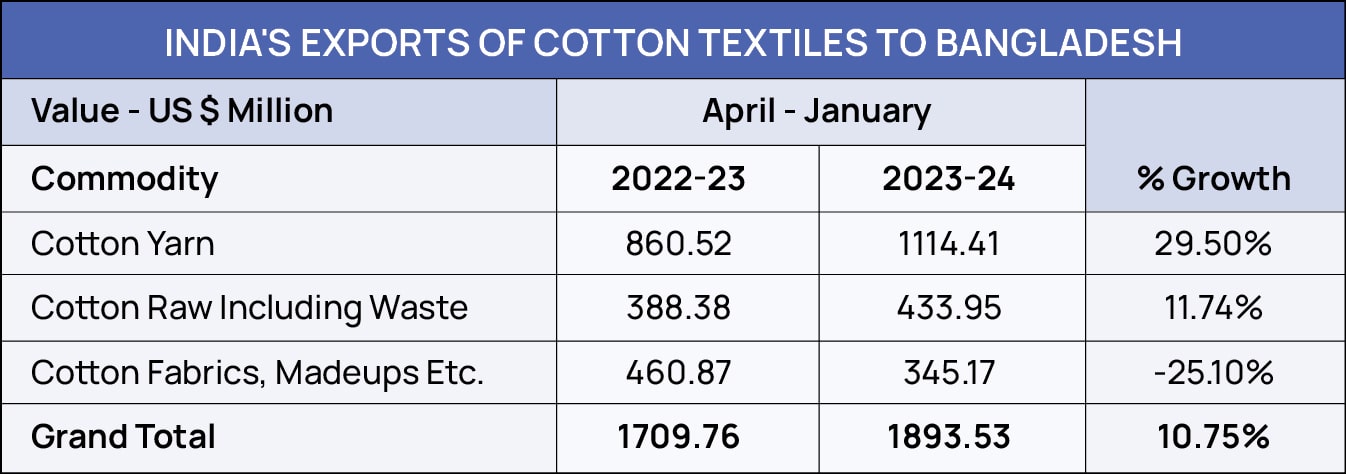

But things have been brewing on the other side too. Bangladesh, even before India’s move, had taken steps that strained trade ties. The interim regime led by Chief Advisor Muhammad Yunus also halted yarn imports from India via land ports, citing infrastructure limitations.

Currently, yarn imports from India are allowed through seaports and four land ports – Benapole, Sonamasjid, Bhomra and Banglabandha.

Bangladesh’s industry leaders, including BGMEA’s former VP Abdullah Hil Rakib, have voiced their apprehensions about the potential disruption of the supply chain, rising production costs and the impact on Bangladesh’s competitiveness in the global apparel market. While larger factories can source materials through seaports or local suppliers, smaller manufacturers often lack these alternatives.

Along with yarn, Bangladesh also depends on India for cotton, fabrics, handloom products and various chemicals.

For instance, Bangladesh imports over US $ 3 billion worth of cotton annually and more than half of that comes from India. In FY ’23, Indian cotton imports stood at US $ 1.92 billion, rising sharply to US $ 2.36 billion in FY ’24.

The draw of Indian imports isn’t just cost, it’s time. In today’s high-stakes global supply chain, time is often the most valuable commodity as retailers have slashed their lead times from 90 days to just 45.

This puts Bangladeshi exporters under immense pressure. For example, cotton imported from Africa, Latin America or the US can take at least 35 days to reach Chattogram port and another 15 days to arrive at textile mills. That’s the entire 45-day lead time gone, before production even begins.

In contrast, cotton from India takes just 2-3 days to be delivered and it’s cheaper. That time-saving edge has long been a lifeline for Bangladeshi manufacturers, helping them stay competitive on the global stage.

The stakes aren’t one-sided. India is also a key market for Bangladesh. Just last year, during political unrest in Bangladesh, businesses in Surat were facing monthly losses of around Rs. 100 crore. Surat and parts of south Gujarat supply textile products to Bangladesh.

Given that a significant portion of exports to Bangladesh fall outside the purview of the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) agreement and that most imports from Bangladesh enjoy zero tariffs, the current face-off presents a serious challenge to the trade dynamics between the two nations.

As tension mounts, the impact is also visible in people-to-people connections. Earlier, India used to grant nearly 8,000 visas to Bangladeshis every day. Now, that number has dropped to around 1,000, as per recent reports following the fall of the Sheikh Hasina regime.

This also casts a shadow on what was once a growing model of regional connectivity.

The industry is now waiting for a thaw in relations between the two countries, but the recent meeting between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Muhammad Yunus on the sidelines of the BIMSTEC Summit in Bangkok was not something to write home about.

| Key Achievements in Connectivity

Rail Links Restored: Agartala-Akhaura (Inaugurated in November 2023) – New route to India’s Northeast Haldibari-Chilahati (Reopened 2021) – Enhances cross-border connectivity Other active rail corridors: Petrapole-Benapole Gede-Darshana Singhabad-Rohanpur Radhikapur-Birol Passenger Trains: Maitri Express Bandhan Express Mitali Express These trains connect India and Bangladesh, making travel seamless. Road Connectivity: Bus services linking Kolkata, Agartala and Guwahati with Dhaka and Khulna. River-Based Transit Protocol on Inland Waterways Trade and Transit (PIWTT) (since 1972) supports cargo and cruise movement, boosting trade efficiency. Seaports Chittagong and Mongla Ports operationalised in 2023. These enable faster, cheaper cargo movement to and from India’s Northeastern states. Future Projects Mongla Port Development and Northeast Road Network Connectivity Improvement projects are crucial for enhancing infrastructure. There are concerns about slow progress or delays, but these remain vital for the region’s growth. |